The engineer Curt Fischer pioneered the development of movable work lights with steerable light. In 1923, he began producing his luminaires, for which he had previously launched the Midgard brand. In 2015, David Einsiedler and Joke Rasch took over the traditional company, restructured it and moved it to Hamburg. Under their management, new editions of important luminaires are created that are manufactured with original tools, as well as current new developments such as the Ayno, which continue the pioneering character of the brand into the present. The collaboration with designer Stefan Diez has helped Midgard develop from a traditional engineering company into a pioneering contemporary brand.

By Heike Edelmann

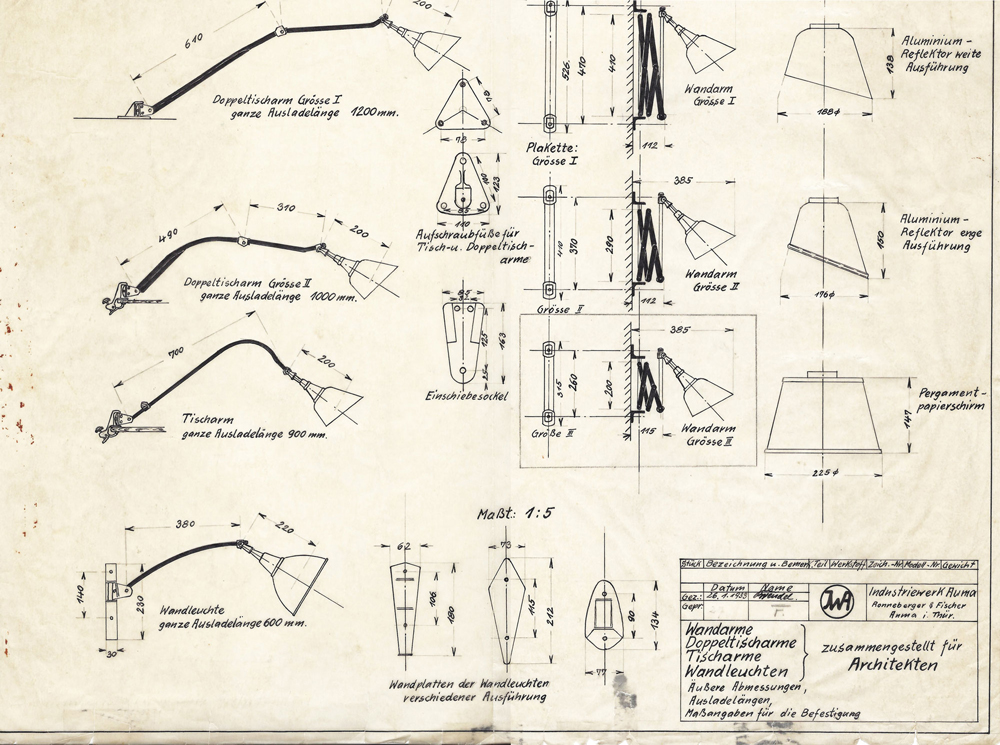

Electric light that can be precisely aligned to illuminate workplaces in factory halls without shadows was a groundbreaking innovation at the beginning of the 20th century. As early as 1919, the engineer Curt Fischer received a patent for his first movable luminaire. It was initially intended to simplify work in his company. At that time, Industriewerk Auma Ronneberger & Fischer was a supplier to the Thuringian porcelain industry. At that time, hanging industrial lights were common, with the result that workers themselves cast shadows on the workpiece they were working on. Fischer recognised the problem and used his extraordinary creativity to design a completely new solution – the first luminaires with steerable light. Initially, he manufactured them for his own use, but other companies were also interested in his invention and wanted to use the innovative luminaires. So Curt Fischer registered the Midgard trademark in 1922 and the following year – after the hyperinflation – began to mass-produce his light sources that could be adjusted with just one hand. From the context of the workshop, Midgard luminaires quickly moved into offices and living rooms. Fischer continuously expanded the portfolio, for example with the Midgard modular luminaire system. He also perfected the joints and shades of his luminaires and received patents for many of his innovations.

At the Bauhaus, Midgard luminaires were appreciated

The new, well-designed light sources also caused a sensation in the architecture and design scene of the 1920s. Fischer corresponded with Walter Gropius and supplied the Bauhaus in Dessau. His luminaires were represented in the Werkbund housing estate in Stuttgart in 1927 as well as at the Berlin Building Exhibition in 1931. Midgard luminaires were used in the studios or flats of Bauhaus directors Walter Gropius, Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, among others. Bauhaus masters such as Lyonel Feininger, Marcel Breuer and Gunta Stölzl appreciated them in their environment, as did Wilhelm Wagenfeld and Marianne Brandt, who designed important lamps themselves. Many other avant-garde creatives from the fields of architecture, typography, film and dance were also enthusiastic about Midgard luminaires as early as the 1920s.

The reason for this was probably the special efficiency and precision of the Type 113 luminaire in combination with an elegantly curved steel tube, which was increasingly used in new furniture at the time. It also literally outshone many designs from the Bauhaus Dessau.

Midgard as an export article of the GDR

In GDR times, the state took a stake in the Auma industrial plant from 1963, and in 1972 the company was completely expropriated and transferred to national ownership. Fischer’s designs continued to be used, but the luminaires were manufactured with inferior materials. After Curt Fischer’s death in 1956, his son Wolfgang Fischer took over the management of the company, and even after the expropriation, he remained the plant manager. He renewed the patent and trademark protection at his own expense. Already in the early 1950s, he encouraged his father to work on the spring-loaded principle. The result was the spring-loaded luminaire, an export article of the GDR, whose material and workmanship quality steadily deteriorated over the years. It was sold to Western European countries far below the manufacturing costs, the main customer being the Swedish Ikea group. In 1990, the company was transferred back to the family. Wolfgang Fischer was soon able to lead his company again, but the market situation after reunification was confusing. Luminaire manufacturers faced additional challenges with the switch to LED lamps. Was semiconductor technology now more important than the mechanical construction of a luminaire? Convincing answers had to be found. After reunification, the fame of the Midgard brand had faded both in West Germany and abroad; only a few connoisseurs were still aware of it. Even a daughter of Wolfgang Fischer’s committed and courageous attempts to revive the brand could not change this.

Re-launch of branded products in Hamburg

Around this time, David Einsiedler expanded his collection of historical work lamps. In the process, he became aware of old Midgard luminaires by chance, whose quality and construction excited him. He got in touch with the third generation of the Fischer family and, together with his wife Joke Rasch, took over the traditional company from Thuringia in 2015. Both were so convinced by the idea of setting up their own business producing Midgard luminaires that they gave up their permanent jobs. David Einsiedler and Joke Rasch restructured the company and today they produce historical designs by Curt Fischer on original tools. They also produce reeditions of Curt Fischer’s articulated lamps in Hamburg, and many traditional suppliers are involved.

Original tools for the production

In 2017, Midgard relaunched Curt Fischer’s machine lamp, a modular and freely configurable system. The spring-loaded luminaire is now also being recreated using original tools. In 2019, the Type 113 luminaire used at the Bauhaus appeared as a limited reedition using original techniques and materials, and following the K831 pendant luminaire once manufactured by Kandem, the K830 wall swivel luminaire, designed by designer Werner Glasenapp in 1931, was relaunched at the end of 2022. All these new editions of important historical luminaires meet today’s demands in terms of function, design and lighting technology.

Sustainable and innovative – the iconic Ayno

Under the direction of Einsiedler and Rasch, innovative new luminaires are also created, such as the Ayno family, which was awarded the German Sustainability Award for Design as a “pioneer”.

With the Ayno, industrial designer Stefan Diez created the first new Midgard luminaire since the 1950s. The innovative power of this new luminaire family is entirely in keeping with the company’s tradition as a manufacturer with a pioneering spirit. Ayno takes up Curt Fischer’s design ideas and translates them into the present, reduced to the essentials and with a high level of design. The central feature of the floor, table and wall lamps is a fibreglass rod that is stretched into an arc by its lamp cable. The inherent tension of the rod ensures that the luminaires manage entirely without joints. The flexible rod of the Ayno is bent into the desired position and the light is directed to where it is needed simply by continuously moving the two adjustment rings on the foot and head sections. The radius of the arc can be varied as desired by means of the rings, the fine adjustment is then made via the swivelling lampshade with integrated LED.

Part of the concept is that the luminaires in this collection are very light and consist of few components. The main components of the luminaire are made of steel, fibreglass and plastic and can therefore be recycled. Midgard avoids long supply and transport chains by purchasing the components worldwide on local markets instead of sending fully assembled luminaires around the globe. In addition, the Ayno is one of the first LED luminaires that users can repair themselves without tools, thereby extending its service life. Thus, the new product range continued Curt Fischer’s tradition of producing pioneering and future-oriented luminaires in a contemporary way. Midgard has made the transition from a traditional engineering company to a contemporary brand for the contract and residential sectors, with a mix of true-to-the-original reissues and exemplary new developments. Along with this, the pioneering company cooperates with a contemporary designer in the design for the first time.

More on ndion

More articles on brands..

Share this page on social media: