The sea, the Arctic, the forest, the lithium plant. In the face of elemental upheavals within our human-altered landscapes, designers are leaving the ordered environment of the design studio and the transdisciplinary space of the laboratory. They take the risk of developing a new design language “in the field” in the open system, together with material cycles, other species and damaged ecosystems.

By Rasa Weber.

Stay restless

In the course of the current ecological and socio-political crisis, design is confronted with a completely new question: How can design, which is classically committed to an industry-driven paradigm and works in a solution-oriented way, counter the current “catastrophic times” (Stengers 2015) with new strategies of ecological agency?

As design scholars Claudia Mareis and Nina Paim so aptly point out in their recent collective publication Design Struggles (2022), design’s task is to reinvent the discipline for the 21st century, emancipating itself from old power- and production-oriented principles of industrial modernity. According to biologist and philosopher of feminist theory and technoscience Donna Haraway, it is our duty as designers to “stay restless” (Haraway 2016) and fully engage with the impassability of a shaken modernity and the changing times of ecological change. To remain restless – that means to expose ourselves to a troubled, dislocated, human-shaped and deformed, fragmented environment. And it means listening. Listening to anthropocentric environments while having the courage to collaborate with them within open and chaotic systems is what constitutes the “New Sensibility” of design.

Learn to Listen

In bright yellow high-water trousers, a hooded person, like an astronaut, rises from the milky whiteness of a toxic lake. In her photographic work, the artist Catherine Hayland goes on the trail of lithium mining at the SQM plant in the Chilean Atacama Desert. The rare mineral, which, as the most important fuel of our digital world, leaves its mark on landscapes and lifeworlds, gapes as a toxic scar in the desert. Atacama itself is considered the driest place on earth. Seen from the air, however, the mining area is a colourful patchwork of highly toxic canary yellow and tropical turquoise. Hayland by no means remains a neutral observer here, but stages people as part of this polluted landscape. Humans are literally knee-deep in the lithium-yellow scoop pools that cut a swathe through the snow-white sand mountains of the mining areas. The photographer confronts us with the toxic beauty of an anthropocentric natural cultural landscape that has become uninhabitable.

In general, field research still seems to be an underrepresented method for design. As a consequence, more and more designers are using methodologies from anthropology and biology to explore environments right on their doorstep or in remote regions. In practice-based collaboration and theoretical discourse, disciplinary boundaries are becoming increasingly porous.

The environment is also the focus of designer Emilia Tikka’s latest work, “Mnemonia”. Together with reindeer herders, she traces the declining landscape of the Sami people in northern Fennoscandia. The designers Laurin Kilbert and Johanna Schmitz pursue a similar approach as the Symbiotic Spaces Collective, but in more accessible landscapes. In collaboration with the designer and anthropologist Luise Stark, the collective develops their “Perception Walks”, which focus on the perception of our local environment. The concern to understand the environment not only as a source of raw material exploitation, as a malleable landscape, as a territory to be conquered and a playground of socio-political power interests, leads our discipline to expose itself to open ecological systems and, in a sense, to eavesdrop on them.

The English concept of “ecological attunement” (Despret 2008, Lipari 2014, Franinović & Kirschner 2021) can be groundbreaking here. “Attunement” refers to tuning into a context, to entering into resonance with the world (Rosa 2019), which may sometimes appear threatening and alienated to us. In the original musical horizon of meaning, however, “attunement” as a mood should not be misunderstood at all. “Attunement” does not denote the duty to subordinate oneself harmonically to the instrumental structure. After all, the (social and musical) mood can also be really bad. Rather, attunement to environments presupposes attentive listening to the dissonances, ruptures and upheavals of the “Patchy Anthropocene” (Tsing 2019).

Die Designer*Innen Sandra Stark und Joe Lockwood verfolgen solch eine Strategie des Lauschens. Ihre Methode des „Nature Journaling“ haben sie den Biolog*innen Paula Harvey und John Muir Laws entliehen, und deren perzeptive Schule der biologischen Feldforschung auf die Methodiken des Designs übertragen. Ebenso schlägt der israelische Designer Daniel Metcalfe mit seinen „Multispecies Design Cards“ eine Neustrukturierung des Designs im Sinne des Entwerfens mit mehr-als-menschlichen Akteur*innen vor. Auch der Fachbereich des Interaction Design an der Zürcher Hochschule der Künste geht der Frage nach, wie das Design als Kollaboration mit Umwelten neu verstanden werden kann. Innerhalb der von Karmen Franinović, Roman Kirschner und Rasa Weber entwickelten „Sensing Exercises“, wenden die Designer*Innen Übungen wie „Environmental Scanning“ und „Deep Listening“ an, um die Welt multisensoriell zu erfassen und zu übersetzt. Die umfassende Aufgabe des Zuhörens, als multisensorischer und phänomenologischer Akt der Wahrnehmung, adressiert alle unsere Sinne: das Hören, Sehen, Riechen, Schmecken und Fühlen. Wie die Komponistin und Pionierin des Lauschens, Pauline Oliveros, es in ihren „Sonic Meditations“ (1974) formulierte: „Mache einen Spaziergang bei Nacht. Laufe so leise, dass die Sohlen deiner Füße zu Ohren werden.“ (“Take a walk at night, and walk so silently that the bottoms of your feet become ears”).

The designers Sandra Stark and Joe Lockwood pursue such a strategy of listening. They borrowed their method of “Nature Journaling” from the biologists Paula Harvey and John Muir Laws and transferred their perceptive school of biological field research to the methods of design. Likewise, the Israeli designer Daniel Metcalfe proposes a restructuring of design in the sense of designing with more-than-human actors with his “Multispecies Design Cards”. The department of Interaction Design at the Zurich University of the Arts also explores the question of how design can be newly understood as collaboration with environments. Within the “Sensing Exercises” developed by Karmen Franinović, Roman Kirschner and Rasa Weber, the designers use exercises such as “Environmental Scanning” and “Deep Listening” to grasp and translate the world in a multisensory way. The comprehensive task of listening, as a multisensory and phenomenological act of perception, addresses all our senses: hearing, seeing, smelling, tasting and feeling. As the composer and pioneer of listening, Pauline Oliveros, put it in her “Sonic Meditations” (1974): “Take a walk at night, and walk so silently that the bottoms of your feet become ears”.

Of worms, spiders and other inhabitants

A textile fabric comes to life. Silkworms tirelessly spin their cocoons on a filigree, white mesh of textile fibres. The animals weave and consolidate a man-made structure. In 2020, the designer and founder of the “Mediated Matter Group” (MIT – Lab), Neri Oxman, presented her “Silk Pavilion II”, as part of a solo exhibition at MoMA New York. The caterpillars were part of the installation and busily completed the designer’s architectural brief as the exhibition progressed. Perhaps some found their way onto the visitors’ coats. Perhaps others were completely enclosed in their cocoon. But who actually asked the caterpillars if they wanted to live out their lives in a sterile exhibition space? And what distinguishes the spinning of a pavilion designed for humans from the production of silk for the textile industry?

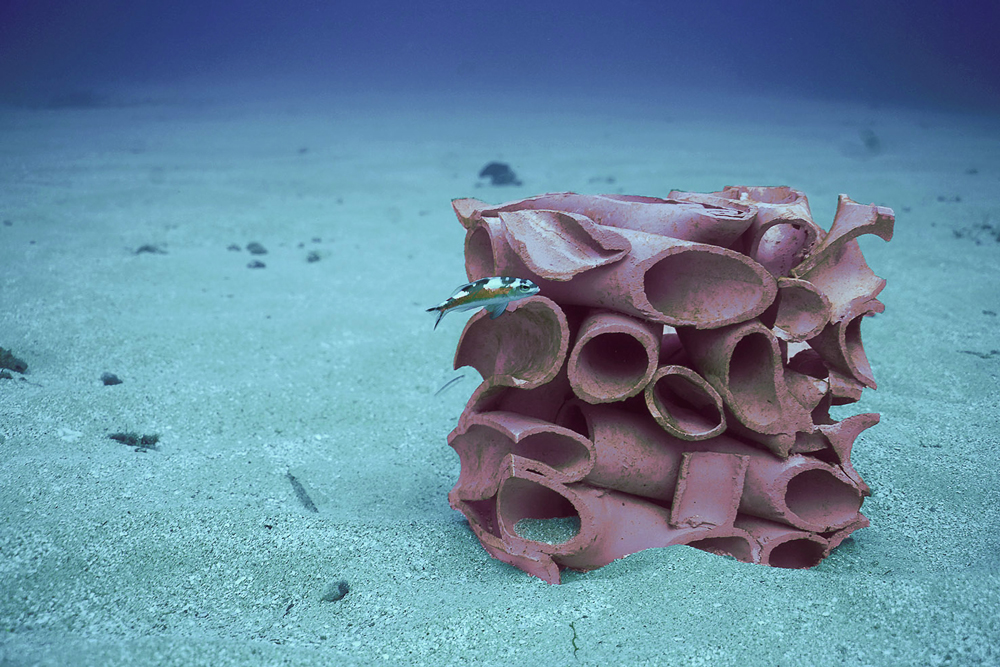

A thought experiment: A wooden sphere stands elevated on metal feet in a clearing in Brandenburg. On closer inspection, we see the thin fabric of tree bark from which the structure is woven. The pavilion smells of resin. Inside, the sounds of the forest can only be heard muffled. Is this a house? And if so, who inhabits it? A refuge for hikers perhaps, a nest for robins, or a storage place for squirrels. The “Bark Sphere” pavilion by designer Charlett Wenig oscillates between human dwelling, cave, nest and experimental prototype. With her research project on tree bark, supported by the Max Planck Institute for Colloids and Interfaces, the designer brings the material back to its place of origin. The forest as interlocutor about the design object. The forest inhabitants as recipients and correspondents of the man-made installation. What would happen if Neri Oxman’s “Silk Pavilion” had to stand up not to the museum but to the forest as situational counterpart? Would the silkworms choose a different place for their cocoons? Would spiders spin their webs instead, an oak processionary moth wrap its clutch, a blackbird convert the filigree nest in its favour or a marten gnaw the textile? The dynamics of the environment can hardly be planned. Where design objects find their way into the open system, chaos and the unplanned are inevitable. The designers of the Symbiotic Space Collective know this, too, and have designed their 3D-printed architecture “Symbiotic Spaces in Hildesheim” explicitly not for humans, but for insects and creatures of local shallow waters.

In a design process that takes into account more-than-human actors in open environments, the clearly defined roles of the designer as author and the human as the sole user of the design interventions break down. Designing with and in the environment requires that we question the authority of the designer and are willing to open up both the design process and the use of our designed environments to a multiplicity of living beings.

Getting to the Bottom of the Sea

As a designer and diver myself, I work on material processes and their impact on the environment. I am driven by the question of how we as designers can think and realise new, post-extractive models of design together with our planetary fabric, which is permeated by humans. This question brought me to the ocean, the largest life-giving (Helmreich 2009, Hessler 2019, Latour 2019) and dramatically transforming (Åsberg 2020, Jue 2019) system on our planet. Together with biologists from the Max Planck Institute for Behavioural Biology (Jordan Lab), I spend most of my fieldwork below the surface of the sea, in a marine research institute in northern Corsica. Here I am an alien: a designer among biologists. A diver in the sea. I enter a marine environment in which we humans are only able to survive with the help of technological prostheses, in a sense as “cyborgs” (Haraway 1985). Sensory attunement to the sea is a process mediated by the tools of diving. As a diver, I have to adjust my sensory perception to an alien, aquatic environment in a completely new way. I learn to see, hear and synchronise my design activity sub-mare with my breath in a new way. Inspired by the “Biorock principle” of the German-American architect and diver Wolf Hilbertz (1970) and his colleague Tom Goreau, I want to use an electrolysis process to make limestone grow beneath the surface of the sea. In this way, filigree steel meshes slowly create mineralised surfaces that will provide a habitat for other marine life forms (corals, sponges, algae) in the future. As a designer, I not only design in the sea, but try to give the sympoietic (Haraway 2016) growth processes of the marine biome the decisive voice in my designs. I understand the slowly growing structures as “interspecies architecture”. They are reef, breeding ground and human attraction at the same time.

The sea, a habitat undergoing radical transformation, offers such an experimental zone for design in and with anthropocentric environments. The aquatic medium invites designers to engage with complex biological networks and conduct field research beneath the surface of the sea. A few designers are already following this path and working as divers in the open system of the ocean: Marie Griesmar is working as a designer and diver within her NGO Rrreefs e.V. on the restoration of reefs based on a 3D-printed building block. The Danish studio Superflex is working on fish architecture in collaboration with biologist Anja Wegner under the title “Pink Elements” and French designer David Enon is growing generic design furniture as underwater reefs with his “Mineral Accretion Factory”.

The “new sensibility” in design is an adventurous undertaking that continuously pushes us designers to our disciplinary limits. Ecological growth processes span time horizons far beyond human imagination. And not all species are ready to accept our invitation to cooperate. The “New Sensibility” is a modest gesture that contrasts the limitations of human exclusivity (Haraway 2007) in classical design with a collaborative model of shared survival in troubled times.

Sources:

Åsberg, Cecilia: A Sea Change in the Environmental Humanities, in: Ecocene. Cappadocia Journal of Environmental Humanities, Jg. 1, 2020, edition 1, p. 108-122.

Despret, Vinciane: The Becoming of Subjectivity in Animal Worlds, in: Subjectivity, Jg. 23, 2008, Issue 1, p. 123–139.

Franinović, Karmen & Kirschner, Roman: Interacting in Entangled Environments, in: Not at Your Service, Manifestos for Design, edited by Matter, Hansuli und Franke, Björn, Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, 2021, p. 249-260.

Haraway, Donna J.: When Species Meet. Posthumanities, vol. 3, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Haraway, Donna J.: Unruhig bleiben. Die Verwandtschaft der Arten im Chthuluzän, Frankfurt am Main, Campus Verlag, 2018.

Helmreich, Stefan: Alien Ocean: Anthropological Voyages in a Microbial Sea, 1. ed., Oakland, University of California Press, 2009.

Hilbertz, Wolf: Towards Cybertecture, in: Progressive Architecture, 1970, S. 98-103.

Jue, Melody: Wild Blue Media: Thinking Through Seawater, Durham, Duke University Press, 2020.

Latour, Bruno: Foreword, in: Prospecting Ocean, ed. by Hessler, Stefanie, Cambridge, London, The MIT Press, 2019, S. 11-13.

Lipari, Lisbeth: Listening, Thinking, Being: Towards an Ethics of Attunement, University Park, The Penn State University Press, 2014.

Lowenhaupt Tsing, Anna: Patchy Anthropocene: Landscape Structure, Multispecies History, and the Retooling of Anthropology. An Introduction to Supplement 20, in: Current Anthropology, 2019, issue 20, p. 20.

Mareis, Claudia und Paim, Nina (ed.): Design Struggles. Intersecting Histories, Pedagogies, and Perspectives, 1. ed., Amsterdam, Valiz, 2021.

Oliveros, Pauline: Sonic Meditations, Chicago, Half Letter Press, 2017.

Stengers, Isabelle: In Catastrophic Times: Resisting the Coming Barbarism (Critical Climate Change), Lüneburg, Open Humanities Press, 2015.

More on ndion

More articles on design and research.

Share this page on Social Media: