To some, he was a bad boy, but to Steve Jobs Hartmut Esslinger was exactly the kind of designer Apple needed. Esslinger and his team at frog design not only shaped Apple’s design language in the early 1980s, but gave the brand a unique aesthetic that helped pave the way for its ongoing success.

Von Thomas Wagner

A Beetle, a Ferrari or a Porsche? In his biography of Steve Jobs, Walter Isaacson recounts a discussion in 1981 between Jobs and James Ferris, then Apple’s head of design. The discussion centred on what the Macintosh they were developing should look like. Jobs thought it should be classic, like a VW Beetle. Ferris thought it should be sleek, like a Ferrari. Jobs replied: “More like a Porsche. At the time, no one in the computer industry cared more about product design than Steve Jobs, who drove a Porsche 928. On the face of it, Apple computers had to be different from the boring business boxes favoured by IBM, but also from what Apple had achieved up to that point with the Model II and III. Although the story of Snow White, the Apple and the Black Forest has been told many times before, it is worth repeating.

Codename Snow White

Although Jobs wanted to focus on the Macintosh, he also wanted a unified design language for all future Apple products. According to Isaacson, a “world-class designer” was to be found through a competition, with the winner playing a role for Apple similar to that of Dieter Rams for Braun. The project was codenamed “Snow White”, a likely reference to Braun’s classic SK 4, known as the “Snow White Coffin”.

The winner of the competition was Hartmut Esslinger. Having founded Esslinger Design in Altensteig in the Black Forest in 1969, he was known for his designs for WEGA and, after the brand was acquired by Sony in 1974, for his work with the Japanese company. In 1982, “Esslinger Design” became “frogdesign“. Legend has it that when Steve Jobs visited Esslinger in the Black Forest, he was impressed not only by the designer’s passion but also by the way he drove his Mercedes at high speed.

Apple Should Become the Greatest Brand in the World

Decades later, Esslinger described his first meeting with Steve Jobs with characteristic self-assurance: “He was open enough to admit that Apple didn’t stand out enough from the competition, but he also said that he wanted to change that, and that’s why he was looking for a top designer. When I asked him about his bigger ambitions, he just smiled and said: “First, I want to sell a million Macs, and then I want Apple to be the greatest brand in the world. For some inexplicable reason, we both agreed that these goals were absolutely achievable.

The Californian Look

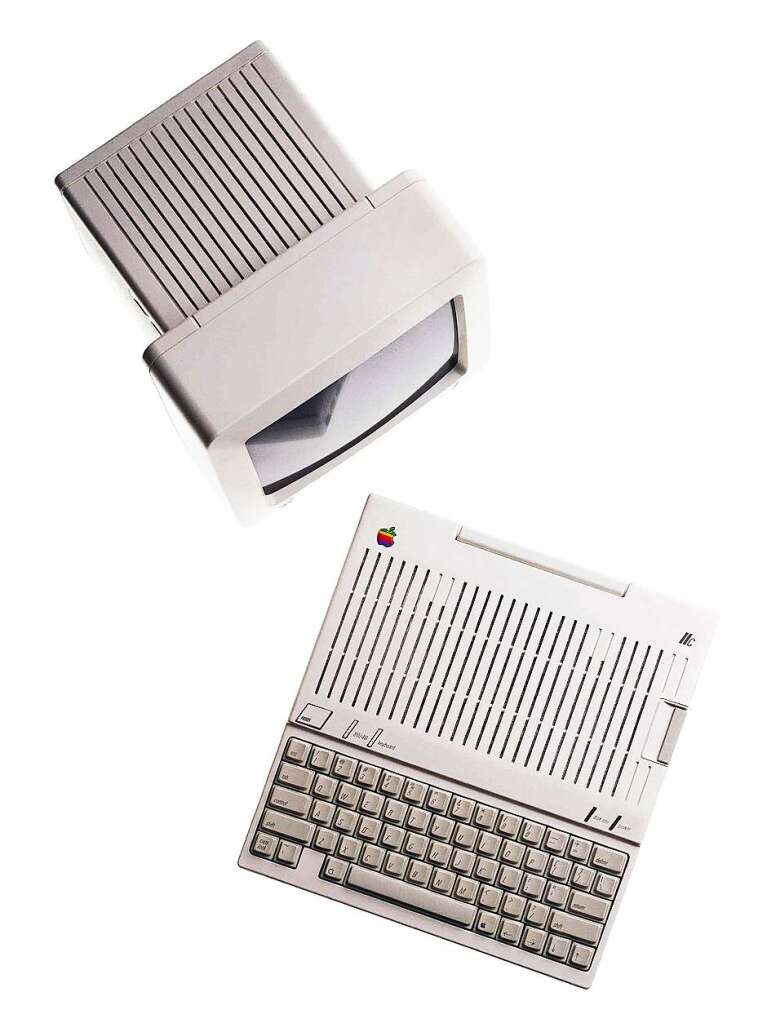

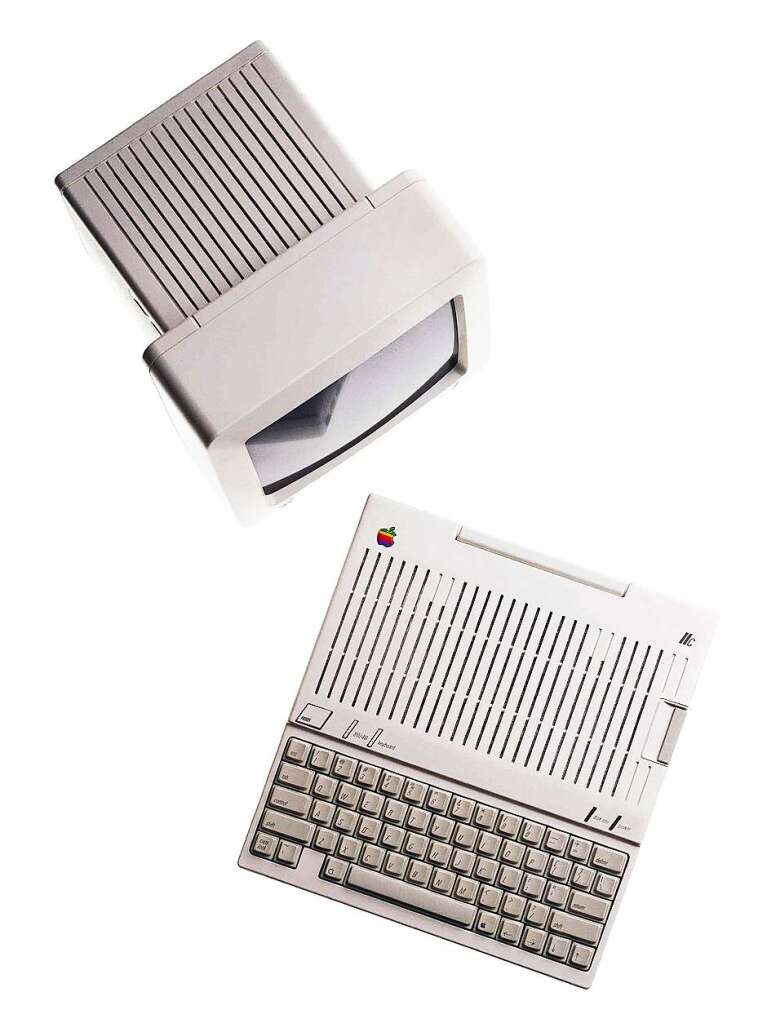

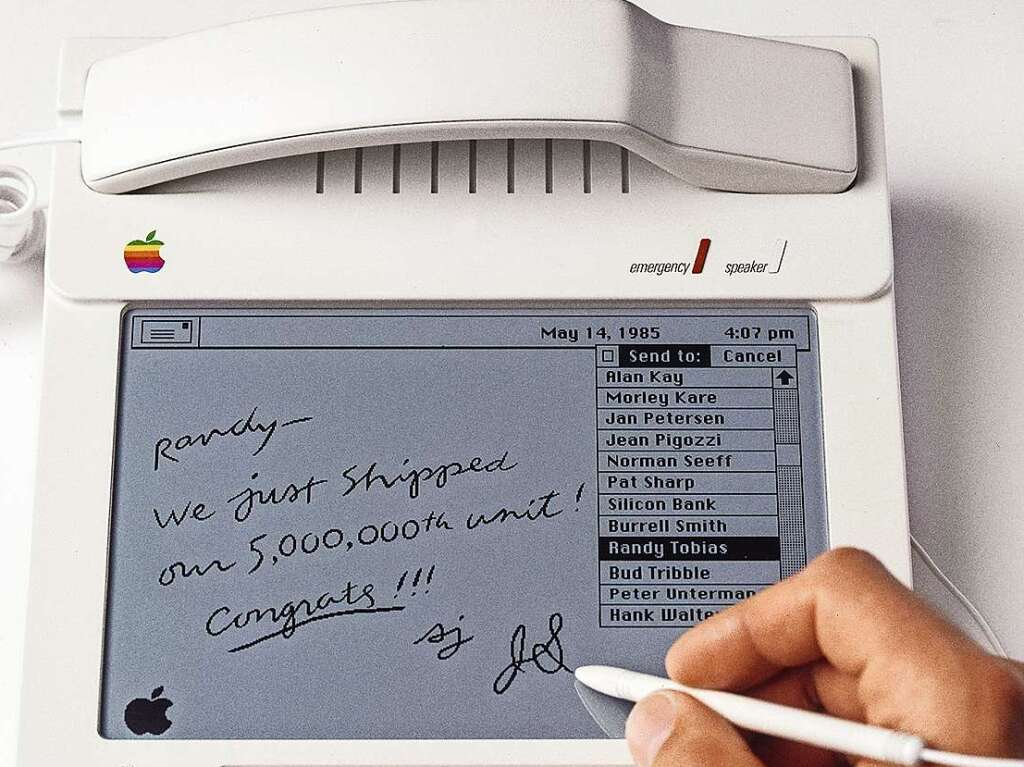

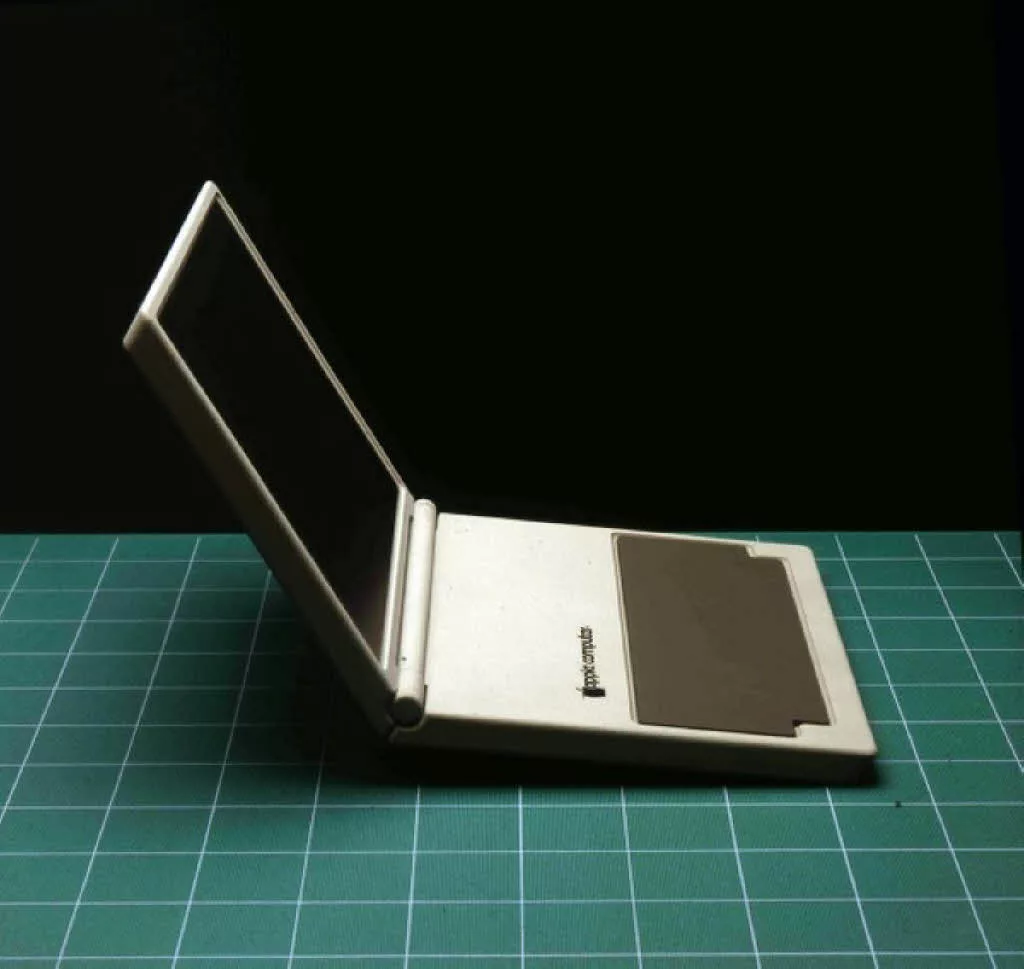

We could go on and on about how Esslinger succeeded in opening up the form and function of industrial design to emotional elements and cultural signals (which were also influenced by postmodernist discussions about the relationship between high and low culture), but the fact is that he rightly embraced the West Coast spirit and a “Californian look” that tapped into the cultural energies of Hollywood movies, pop music, gentle rebelliousness and sex appeal. In fact, he rightly embraced the West Coast spirit and a “California Global Look” that tapped into the cultural energies of Hollywood movies, pop music, gentle rebellion and sex appeal. The impulses he set in motion paved the way for Apple’s later success. Esslinger designed no fewer than 40 different product models to present his concept, and when Jobs saw them, he immediately exclaimed, “That’s it! The Snow White look, which was immediately adopted for the Apple IIc, consisted of white enclosures with slim, rounded edges and delicate, evenly spaced vents that gave the surfaces texture and turned their function into a graphic element. Jobs offered Esslinger a contract if he was prepared to move to California. Esslinger later modestly but accurately described the handshake between them as “the beginning of one of the most consequential collaborations in the history of industrial design”. In mid-1982, Esslinger opened his company, frogdesign, in Palo Alto. The contract with Apple was worth $1.2 million a year. To strengthen the brand, every Apple product from then on bore the inscription “Designed in California”. The frog sitting on the apple had taken a giant leap forward.

Turbulent Times

It was also surprising that after Jobs’ dismissal from Apple, Esslinger went to work for his new company NeXT – or rather, was allowed to work for NeXT. The likelihood of Apple agreeing to this was extremely low, as the two companies were in litigation against each other. “But that didn’t stop Jobs from trying,” says Isaacson. In early November 1985, exactly five weeks after Apple filed suit against him, Jobs wrote to Eisenstat asking for a release. I talked to Hartmut Esslinger over the weekend and he suggested that I write to you about why I want to work with him and frogdesign on the new products for NeXT. Surprisingly, Jobs’ argument was that he didn’t know what Apple was working on, but Esslinger did: NeXT had ‘no knowledge of the current or future direction of Apple’s product design, and this is true of other design firms we may work with. It is therefore possible that similar-looking products may be developed inadvertently. It is in the best interests of Apple and NeXT to rely on Hartmut’s professionalism to ensure that this does not happen.

NeXT and the Perfect Cube

Jobs’ audacity paid off. In January 1986, Apple and Jobs reached an out-of-court settlement without financial compensation. In return for Apple dropping the case, NeXT agreed to a number of restrictions. Now that the terms were clear, Jobs courted Esslinger until he terminated his contract with Apple; by the end of 1986, the way was clear for frogdesign and NeXT to work together. It is said that Esslinger insisted on having a free hand: “Sometimes,” Isaacson quotes him as saying, “you have to give Steve a stick”. The task at NeXT proved to be quite complicated. According to Jobs’ specifications, the computer had to be an absolutely perfect cube, each side exactly 30.48 centimetres long – and all at a precise 90-degree angle, not with the slight deviation of a “lift-out slope” to make it easier to remove the castings from the mould. Instead of “snow white”, the case was now matte black. And it had the unmistakable thin joints that had long since become Esslinger’s trademark.

Keep it Simple

The collaboration with Jobs and the development of an independent and in many elements (and device types) forward-looking Apple design profile was and is a milestone in industrial design and a highlight in Hartmut Esslinger’s career. In 2014, he himself published his view of things under the title “Genial Einfach. The early design years of Apple” and provided detailed information on the design process (“Keep it simple”) that helped Apple develop a successful design strategy and product language. Whether, as Esslinger suggests, the Greek tragedy is the model for the design process – with a hero, an antagonist and a hopeless situation – or whether everyone involved in such a project is rather acting in a comedy is anyone’s guess. Regardless of all the more or less tragic heroic sagas, the results of the Snow White process impressively demonstrate how central the enthusiasm for design, a stringent product language and its placement at the centre of the brand were and are for innovative companies – not only in the founding years of an industry and a company that have since changed our world from the ground up.

more on ndion

More on the topic of People in Design and Design.

Social Media