3D-printing promises to revolutionise construction – making it faster, more accurate and more resource efficient. But the construction industry is still dominated by manual labour, analogue processes and site logistics. This is about to change: automated, digitally controlled and with new creative freedom. What can technology really do today – and where are its limits?

by Benjamin Pfeifer

For more than a century, architects have dreamed of building houses the way we build cars or ships. But the reality of construction today is a far cry from Le Corbusier’s idea of a ‘living machine’ based on standardisation and mass production. Concrete is still poured into wooden moulds on site, blueprints are still printed on paper and the drywall builder still waits for the electrician to finish. The efficiency and rationalisation once associated with industrialised construction remain elusive. Now, however, the old idea seems to be reforming under digital conditions – automated, centrally controlled and offering unprecedented design freedom. At least that’s the promise often made in connection with 3D printing: ‘Europe’s largest 3D house, built in just 140 hours’, Tagesschau (20.07.23); ‘A house, six apartments and 118 hours of printing time’, Handelsblatt (28.12.24). For those who believe in the potential of 3D printing in architecture, building a house no longer takes months or even years, but just a few days. But how does 3D printing actually work?

Additive vs. Conventional

While early methods such as stereolithography have been used in industry since the 1980s, 3D printing developed much later. Essentially, 3D printing falls into the category of ‘additive manufacturing’, where components or entire buildings are built up on site, layer by layer, from a viscous material. Depending on the method and application, this material can be based on a range of substances – including concrete, sand, plastic, metal or recycled materials such as waste paper.

In house printing, a specially developed liquid concrete is often used, which is applied to the foundation slab using a printing arm. A computer-controlled nozzle deposits the material along a digitally pre-programmed path, forming walls, partitions or components – all without the need for formwork. The process is guided by a 3D model that defines each step of the printing process. Unlike traditional construction, there is no need for complex formwork or manual intermediate steps. The process is automated, accurate and relatively fast.

More Form, Less Material

This technology-assisted production makes it possible to manufacture components with high dimensional accuracy and complex geometries, which would be difficult or even impossible to achieve using conventional methods. At the same time, it saves material because material is only used where it’s structurally or functionally necessary. In the context of the circular economy, 3D printing plays a key role – additive manufacturing means that only the actual amount of material needed for the component is used. There’s no off-cut waste, no discarded moulds. The mould is flexible, the process is efficient and printing can be done around the clock if required. Even complex shapes such as ribbed structures or honeycomb patterns can be produced with optimum material utilisation – something that is almost impossible to achieve with conventional construction techniques. 3D printing not only advances the principles of industrial construction – automation, rationalisation, prefabrication – but also enhances them through digital control and greater creative freedom. Two recent projects illustrate both the potential and the current limitations of 3D printing in construction.

‘In the context of the circular economy, 3D printing plays a key role – additive manufacturing means that only the actual amount of material needed for the component is used. ‘

Europe’s Largest Print Projects

The data centre building for Heidelberg iT Management GmbH & Co. KG is one of the largest 3D printed buildings in Europe: the shell of the approximately 50 metre long, single-storey building was completed in just 170 hours. Thanks to digital control and on-site fabrication, many traditional steps such as formwork or intensive manual labour were eliminated. At the same time, less material was used because the concrete was precisely extruded layer by layer. The project demonstrates the potential of 3D printing for functional, medium-sized buildings with individual design languages – but also highlights current challenges: the undulating structure of the building placed high demands on the roof design, certified windows for the new type of printed concrete were not available, and full completion still took more than ten months, despite the rapid construction of the shell. In addition, the large size of current printers makes urban applications difficult.

The White Tower by Mulegns

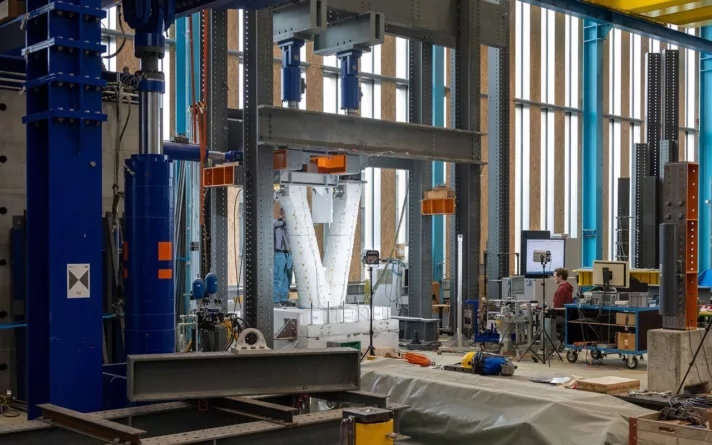

The ‘White Tower’ in Mulegns (2024), developed at ETH Zurich, takes a different approach: the 30-metre-high spatial sculpture consists of 32 individually designed, load-bearing columns with integrated steel reinforcement – a first in 3D printing. Robotic concrete extrusion enables filigree structures with high load-bearing capacity to be created using a minimum of material. Compared to conventional concrete casting, material use was reduced by up to 40 per cent. Modular prefabrication at a nearby facility allows for precise fabrication, transport and disassembly on site. In addition to its striking aesthetics, the project demonstrates how 3D printing enables entirely new approaches to construction – such as combining ornament, structure and support in a single digital design and fabrication process.

Technology Limitations

Multi-storey buildings have long been considered a major challenge for 3D printing – particularly because it hasn’t been possible to seamlessly integrate reinforcement into the printing process. The White Tower of Mulegns offers a pioneering solution: as the concrete is printed layer by layer, a second robot simultaneously places the horizontal reinforcement. The vertical reinforcement is then inserted and filled into hollow channels. For the first time, it is possible to build load-bearing, multi-storey structures using 3D-printed reinforced concrete – but using conventional prefabrication methods. The columns consist of multiple elements: the base and capital are precast concrete, the shaft is the 3D-printed section into which vertical reinforcements are inserted and then grouted.

A Hybrid Future

These two projects illustrate the potential of 3D printed architecture: in particular, the structural shell can be built quickly and with fewer resources, with walls erected in just a few days. However, the technology still has clear limitations. Typically, only the building shell is printed – services, insulation and interior finishes are done conventionally. Material options are limited and the carbon footprint of special concrete remains high. The White Tower shows that, strictly speaking, multi-storey buildings cannot be built using 3D printing alone, but the technology can play a role in the prefabrication of components. High upfront costs, lack of standards and regulatory uncertainty are also slowing down its practical application.

The future of 3D printing therefore lies not so much in a radical reinvention of construction, but in its intelligent integration into hybrid processes. Where standardised workflows, high precision and bespoke shapes are required, the technology can play to its strengths, saving material, speeding up processes and opening up new design possibilities. Particularly in prefabrication, for special components or in heritage restoration, 3D printing can make construction more efficient, resource-conscious and adaptable. The industrial vision of construction is moving a step closer – not as a utopia, but as part of an increasingly digital everyday building reality.

About the ICONIC AWARDS 2025

More visibility, more opportunities – the new ICONIC AWARDS provide a stage for tomorrow’s ideas and projects. They open up networking and business opportunities and pave the way to new markets. They are aimed at architects, interior designers, designers and companies who are shaping the future with visionary projects, innovative products and sustainable concepts.

Submission deadline: 16 May 2025

Share on Social Media