Pioneer, teacher, theorist, enlightener, tango dancer: Gui Bonsiepe designed the famous ‘Opsroom’ in Chile and played a key role in the development of the discipline of interface design. Today he turns 90.

By Fabian Wurm

In his lectures, Gui Bonsiepe likes to quote from Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s book ‘Mr Zett’s Reflections’. Hell, he says, should be imagined “as a place entirely furnished by designers”. Bonsiepe then goes on to say that since he himself belongs to the guild of designers, for better or for worse, he speaks as a “designer of hell”. The former interface design professor’s jokes are serious. But he won over the audience. And his complaint that design has increasingly moved away from intelligent problem solving and is now “largely equated with expensive, exquisite, impractical, funny, formally exaggerated and colourful objects” is not at all sour and without Teutonic fury.

Disobedient and Enlightened

Gui Bonsiepe, who turns 90 today, is a tireless educator and a pioneer of hypermedia design. He is also a sought-after speaker and welcome guest at American universities and international conferences. He has taught for decades, written for magazines and published books, and occasionally worked as a designer. But he is best known as a design theorist – almost more in South America and the Anglo-Saxon countries than in Germany. Just two years ago, a volume of his collected essays, running to almost 500 pages, was published by the British publishing house Bloomsbury. The wonderful title “The Disobedience of Design” is almost a credo: “The Disobedience of Design”. Bonsiepe says that designing means “exposing oneself to paradoxes and contradictions, never hiding them under a harmonising layer, and it also means explicitly unfolding these contradictions”.

From Language to Design

Bonsiepe was a student of Max Bense, the controversial philosopher and science theorist, from 1955. At the legendary Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) in Ulm, he was one of the first to study in Bense’s ‘Information’ department. Bense’s curriculum included writing different types of text, the formulation of everyday texts, but also exercises in style. It was also important to practise techniques of debate and free speech. The “formation of discursive competence”, as Bonsiepe later recalled, was the aim. Bense contrasted the “metaphysical cosiness” of post-war German society with the “disobedience of ideas”, the “beauty of nature” with the “beauty of technology”. The aim was to train the spirit of contradiction. That was one intention, the other was to talk rationally about design and art. Bense was convinced that “aesthetic information” could even be precisely calculated.

Using a student work by Bonsiepe, an abstract pictorial composition, Bense demonstrated how the degree of order could be measured by laying a grid over the picture and statistically analysing the proportions of light and dark values. There is no doubt that this method was mathematically ingenious.

Emphatic Interest in Theory

It was the hour of information theory, cybernetics and calculation: the idea was to replace “ad hoc design” with rationally based design. However, Bonsiepe did not really believe in objective orders and the mathematician Birkhoff’s formula, which Bense elevated to the measure of all things. He quickly recognised the “limits of mathematical techniques”. However, his interest in visual-verbal rhetoric was awakened. And so it remained with his degree at Ulm University, which, as Bonsiepe emphasises, was characterised by “an emphatic interest in theory”. This school had truly earned its reputation as the stronghold of methodology. It was only in Ulm that design emancipated itself from architecture and art and became its own “domain”, says Bonsiepe; he avoids the word “discipline”.

In 1960, Bonsiepe became a lecturer and editor of the HfG magazine “ulm”, which was published in German and English until the end of the university and attracted attention far beyond the university. This publication considered what semiotics, mathematics, physics and the findings of the engineering sciences can contribute to the understanding and development of design. The spectrum was broad. Together with his mentor Tomás Maldonado, who was rector of the HfG at the time, Bonsiepe wrote the treatise “Science and Design” in 1964, which can be read as a key text.

Stirring up Trouble, not Keeping Calm

The sheer range of topics covered in this in-depth presentation is astonishing, showing how far beyond the boundaries of the traditional fields of design they have gone: there is talk of cybernetics and combinatorics, game theory, ergonomics, topology and experimental psychology. The final sequence, however, reads like a manifesto: “The function of the product designer,” it says, “should no longer be to design products that satisfy an already structured need, as is still the case in our free market economy. Rather, the product designer “must be the one who contributes to the structuring of demand, otherwise all that remains is the modest role of helping to preserve existing objects with superficial modifications. The role of the product designer should not be to preserve calm, but to create unrest.

Bonsiepe demonstrated what the function of a product designer can be in concrete terms after the closure of the HfG Ulm in 1968: From then on, he worked as a design consultant in Chile, developing inexpensive furniture for low-cost living and becoming head of the design department of the “Comité de Investigaciones Tecnológicas” (INTEC), an economic development agency of the socialist government of President Salvador Allende. One of his most important design works of those years, part of the Cybersyn project of 1972/73, has long captured the imagination of various publications, including the New Yorker, Der Spiegel and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung (FAS), under the acronym “Opsroom”.

Chile’s Visionary Computer Network

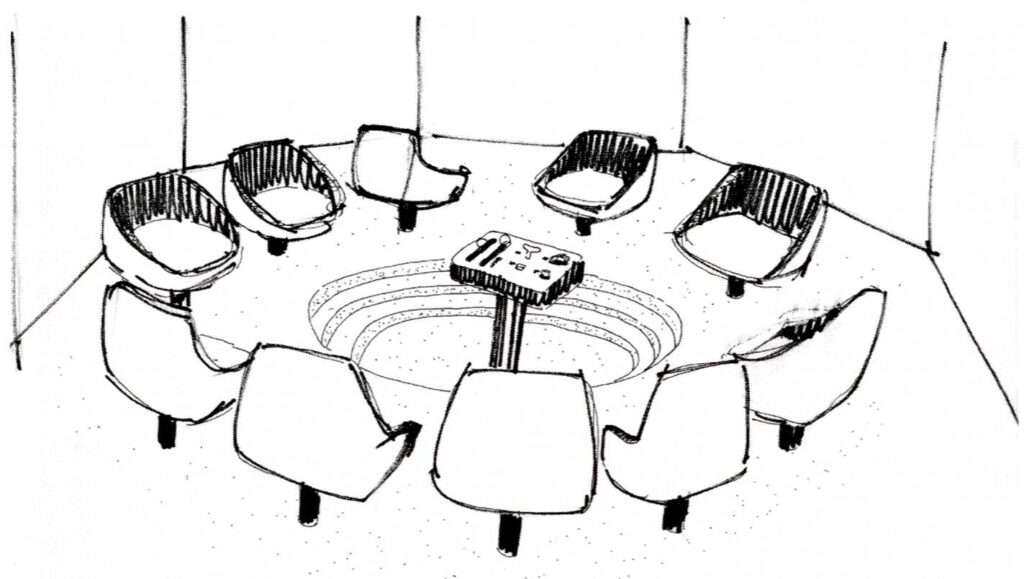

“Workers should be given the opportunity to have a say and autonomy in decision-making. In other words, what was being attempted in Chile long before Silicon Valley existed was a form of data-based politics and direct democracy,” the FAS wrote six months ago. The facts are more sobering: it was primarily about controlling the state economy. The 400 most important factories in the country were supposed to send their key economic figures by telefax to a control room (ops room) where seven decision-makers would meet. Bonsiepe designed a room with white, swivel and orange upholstered fibreglass chairs, with numerous control buttons integrated into the right armrests. Displays were to be placed on the walls, and data from state-owned companies was to be collated on large screens. The economic managers would then be able to react to the constant flow of data, analysed by a computer (IBM 360/50), and quickly decide how to coordinate certain sectors of the economy.

Photo of Opsroom prototype with 7 swivel chairs, Project Cybersyn | © Gui Bonsiepe

Sketch of ‘Opsroom’ with screens | Gui Bonsiepe archive

Sketch of ‘Opsroom’ mmic 10 swivel chairs | Gui Bonsiepe archive

Against Time: Bonsiepe as the Hero of a Novel

Although the Chilean design experiment ended with the violent overthrow of Salvador Allende on 11 September 1973, Bonsiepe stuck to his speciality: the analysis of interfaces and human-machine interaction. From 1987 to 1989 he worked for a software company in Emeryville, California, and in 1993 he was appointed professor of interface design at the design faculty of Cologne University of Applied Sciences. In 1996 he published the book “Interface – Design neu bereifen”.

Bonsiepe defines the interface as “the transformation of data into comprehensible information, the transformation of mere presence – in Heideggerian terminology – into accessibility”. The importance of design is therefore increasing, especially in the context of digitalisation: “In virtual reality, everything is design – the rest evaporates”.

The author Sascha Reh has created a literary monument to Bonsiepe in his novel “Against Time”. Reh’s story revolves around the history of the Chilean Opsroom experiment; the main character Hans Everding can easily be identified as Gui Bonsiepe. Reh describes the designer as a primarily politically active and technically minded person, cosmopolitan and noble by all means, but also very much concerned with keeping his distance. He does not speak publicly about his personal sensitivities and obsessions. Fiction and reality may not be far apart here. Bonsiepe’s students at the Cologne International School of Design, where he taught from 1993 to 2003, were somewhat taken aback when their professor once spoke in a seminar about how much he enjoyed dancing the tango.

More on ndion

More News on People in Design and Design.

Share on Social Media: