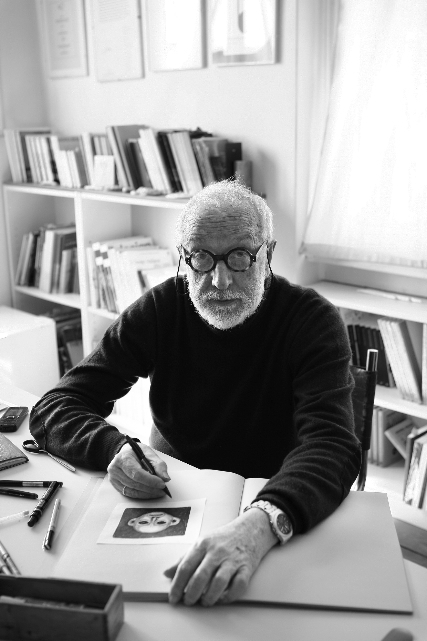

Archizoom, Alchimia, Memphis and on: Andrea Branzi has been involved in many formations of the critical Italian design avant-garde. Whether as a designer or theoretician, he never swam in the mainstream. Now Andrea Branzi has died in Milan at the age of 84.

By Thomas Wagner

Andrea Branzi did not simply swim along in the great shimmering swarm of successful Italian designers of the 20th century. He did test himself and his critical position on design and architecture in various groups (which were resistant, radical and avant-garde) – but nevertheless: it was not the collective formation, but he himself who gave himself and what he designed and formulated a clear direction. Which often meant: He swam ahead and against the current.

Anti-Design and Radical Design

In Florence, where he was born on November 30, 1938, Andrea Branzi studied architecture. In the mid-1960s – in society it was fermenting – the Italian Anti-Design and Radical Design entered the public stage. Questions were asked. Together with Paolo Deganello, Gilberto Corretti and Massimo Morozzi, also university assistants, Branzi founded the “Archizoom-Associati” in 1966. (The name was a combination of that of the British architectural group “Archigram” and that of the magazine “Zoom.”) The group attracted attention with projects such as the urban vision “No-Stop-City,” a fundamental critique of the urbanism of architectural modernism seasoned with irony. With the spread of market capitalism, the thesis went, the city had increasingly taken the shape of a system that was functional in a crude way-which was presented as a flexible architectural grid construction in the form of a plane, seemingly continuous into infinity.

Who controls the built environment?

By means of a critical utopia, the status quo should be questioned, awareness should be raised about who exercises control over the built environment and what role design plays as a conceptual tool in this. Is it no longer architecture that shapes a city, but the commodities that circulate within it? Does whoever designs new commodities design new urban structures and territories? “The real revolution in radical architecture,” Branzi says, “is the revolution of kitsch: mass cultural consumption, pop art, industrial-commercial language. The idea is to take the industrial component of modern architecture to the extreme and thus radicalize it.”

When it came to furniture and objects, Archizoom also attacked the boundaries of prevailing taste with relish, tested new materials, and denounced the narcissism of academic models. How the prevailing functionalism (not only Mies van der Rohe) could be effectively satirized is still demonstrated today by the object-like lounge chair “Mies” from 1969. Archizoom disbanded in 1974. In 1975, together with Ettore Sottsass and Alessandro Mendini, he founded the organization CDM (Consulenti Design Milano), which dealt with new materials and technologies. He was involved for a while with Studio Alchimia (which saw itself as a “post-radical discussion forum”) and also with Memphis, to which he was connected through his friendship with Ettore Sottsass.

A designer with attitude

What was decisive in all of this was that Branzi had less of an impact through the objects he designed than through his attitude toward design as a movens and factor in a society shaped by capitalism. He posited, for example, that capitalist culture had entered a crisis in the 1980s. Long before the swarm noticed that this culture – with, as all can see today, threatening consequences – was heading in the wrong direction, Branzi predicted the end of the myth of progress, which transforms time into a linear function in which everything is constantly changing – or must change. At the same time, Branzi was aware that every new departure, every movement, if it wants to have an effect beyond the day, needs a journalistic underpinning. So in1982 he initiated the founding of the “Domus Academy” (which he headed as vice president until 1987), edited the magazine “Modo” from 1983 to 1987, and published numerous books, essays, and articles on design, urban planning, and architecture. In addition, Branzi, who was honored with the Compasso d’Oro in 1987 for his life’s work as a designer and theorist, taught as a professor at Milan Polytechnic until 2009.

Against functionalism

Instead of understanding the city only as a functional system that breaks down into individual zones that serve living, working, shopping and leisure, Branzi said the city must be thought of as an ensemble of human relationships. He spoke of high-tech favelas because, from his perspective, the city is constantly in motion like a living thing and cannot be controlled. Branzi was thinking of the dynamics of non-European cities, of places that are a symbiosis of urban and agricultural spaces, that change with the seasons and have a lasting effect on the climate. It is not the perfect that points to the future; rather, it is necessary to accept the fragmentary.

With irony against domestication

Branzi’s approach to design changed in the mid-1980s. The elements of a recognizably postmodern aesthetic receded into the background in favor of a “neo-primitivism” that mixes natural and artificial elements. Together with his wife Nicoletta Morozzi, he created a series of clothing and furnishings entitled “Animali Domestici.” Even when thinking about interiors and furniture as landscapes, the postmodern irony still resonated, from which Branzi fed a critique of the existing that goes further than much of what is currently being negotiated in design. To call furniture that recognizably combines industrial and natural forms and materials “pets” is more than just a metaphor for the special relationship we have with nature and things.

Throughout his life, Branzi has resisted any kind of domestication, knowing that it has long dominated the human home and its cities. He never stopped designing critical issues, and he knew that designers, if they want to be socially relevant, must not only follow what the industry tells them to do, but also design thoughtful, critical and aggressive things. Andrea Branzi died in Milan on October 9.

More on ndion

More articles on the topic of design.

Share this page on Social Media: